This morning I received an e-mail from one of my unnamed, and totally unreliable, sources.

Sat 4/29/2017 1:06 AM

TO: Dr. ESP

FROM: Unnamed and Unreliable Source

SUBJECT: WHCA Speech

Attached is a copy of the draft remarks Donald Trump planned to give if he had attended last night’s dinner. Although I cannot divulge how I procured this material, it came in a plain white envelope which only said the following, “SALLY forth. More to come.”

Enjoy.

Normally, I would check the veracity of this kind of document before passing it on. But after listening to Carl Bernstein at the actual WHCA Dinner last night, I heeded his advice. “Our objective as journalists is to get the best obtainable version of the truth.” I can assure you there will not be any better obtainable version of Trump’s speech than this one.

Normally, I would check the veracity of this kind of document before passing it on. But after listening to Carl Bernstein at the actual WHCA Dinner last night, I heeded his advice. “Our objective as journalists is to get the best obtainable version of the truth.” I can assure you there will not be any better obtainable version of Trump’s speech than this one.

Good evening, ladies and germalists. I know I promised to go to a 2020 campaign rally in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania instead of this dinner. Imagine that. Another broken promise. Anyway, that poor city has already been exposed to enough nuclear radiation.

Everyone looks so grown-up tonight. It feels like a senior prom at Trump University. The only difference is the cost of attendance is half what we charge and I don’t get my usual cut of the proceeds. Maybe next year we can hold this event at a Trump property. I understand this year’s theme is “Russian to Judgement.”

So this is what Washington looks like on a weekend. Hard to tell the difference. The House and Senate chambers are empty and Melania is in New York. Melania sends her regrets. She told me she had anything else to do.

Being here isn’t the first promise I’ve broken since occupying the dining room at Mar-a-Lago. I also promised to drain the swamp, hire the best people. So what if there are investigations into criminal charges of some of my staff. I didn’t practice saying, “You’re fired” for nothing. Come to think of it, I’ve gone through more people than the survivors of Uruguayan Air Flight 571 after it crashed in the Andes mountains in 1972. (anticipate groans) Too soon?

Speaking of going through other people, a big shout out to Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey. With friends like Jack, who needs Vladimir Putin and Julian Assange. And the campaign didn’t even have to pay Twitter. I like to think of Twitter as the 7/11 of the internet. Open all night and the potheads who drop in at 3:00 am for munchies make about as much sense as I do.

Speaking of 3:00 am, I just learned North Korea is in a different time zone. Not everyone knows that. So when I get up at 3:00 am, it’s actually 3:30 pm in Pingpong, Putang, whatever. So I can see what Kim Jong-Un is doing 11 and a half hours before it has any effect on the United States. I can’t believe I’m saying this but California is in an even better position. If the North Koreans launch an ICBM, San Francisco has three more hours than Washington to react.

Don’t worry. I have a plan to neutralize North Korea. We just have to wait for the next supreme leader Kim Jong-Deux.

One hundred days. Can you believe it? (anticipate more groans) You folks thought I was going to be a disaster. Isn’t it a little unfair to expect so much so soon? It took W two terms to destroy the economy. I only hope I can be as successful with the environment by the end of my presidency.

In closing, I just want to let you know I am donating my salary for this quarter to the White House Correspondents Association scholarship fund. And I hope you report it in tomorrow morning’s newspapers and on the Sunday talk shows. That way, when I accuse all of you of “fake news,” I will be right.

Good night and good luck.

After reading the draft for the first time, it is rumored Trump sent a note to Melania’s speech writer thanking her for such an original closing line.

For what it’s worth.

Dr. ESP

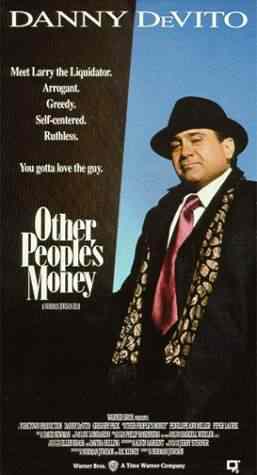

In the 1991 movie Other People’s Money, Lawrence “The Liquidator” Garfield, played by Danny DeVito, selects a struggling family-run business in a small Rhode Island town as his next target. I was reminded of this semi-successful film (Roger Ebert gave it 3.5 our of five stars) as I read a series of news articles this morning which claim Comrade Trump is “on pace to surpass eight years of Obama’s travel spending in one year.” (Source: CNN) Not to mention His Orangeness’ frequent trips to Mar-a-Lago/Winter White House/Southern White House have cost the residents of Palm Beach an estimated $1.7 million to date. Not to mention the New York Police Department estimates they spend $500,000/day on security for Melania and Baron Trump.

In the 1991 movie Other People’s Money, Lawrence “The Liquidator” Garfield, played by Danny DeVito, selects a struggling family-run business in a small Rhode Island town as his next target. I was reminded of this semi-successful film (Roger Ebert gave it 3.5 our of five stars) as I read a series of news articles this morning which claim Comrade Trump is “on pace to surpass eight years of Obama’s travel spending in one year.” (Source: CNN) Not to mention His Orangeness’ frequent trips to Mar-a-Lago/Winter White House/Southern White House have cost the residents of Palm Beach an estimated $1.7 million to date. Not to mention the New York Police Department estimates they spend $500,000/day on security for Melania and Baron Trump.