BLOGGER’S NOTE: If length were not an issue, today’s post would have been, “Everything I Needed to Know about Women Voters in 2020, I Learned from Chuck E. Cheese.”

Wednesday’s ABC/Washington Post poll results in Michigan and Wisconsin affirm what may be the defining difference between this year’s election and 2016, a gender gap of historical proportions. In Michigan, Biden’s lead among women is 24 percentage points. In Wisconsin, 30 percentage points. And the pundits have had a heyday analyzing this defection by females, the latest being the threat to reproductive rights following the appointment of Amy Coney Barrett to the Supreme Court.

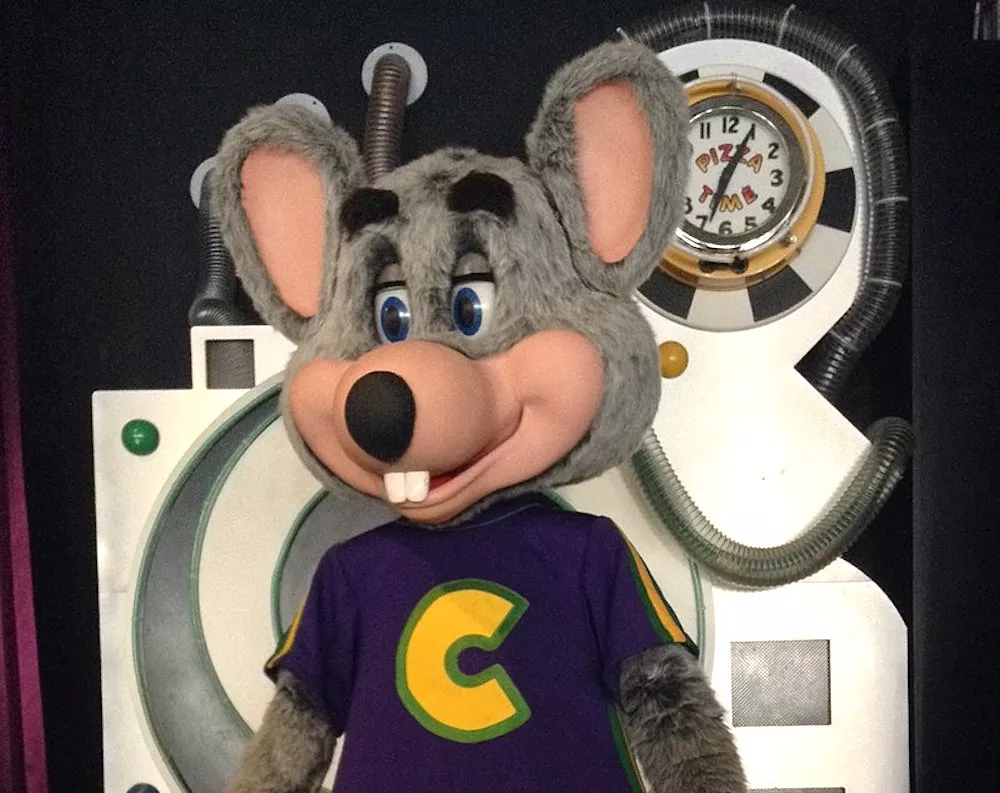

But, as is so often the case, current events are echoes of past experience if only we pay attention. In this case, the ultimate clue that foreshadowed the propensity of women to reject Donald Trump in 2020, lies outside the political area. Instead it is embedded in a 1998 business case involving the licensing of the Chuck E. Cheese (CEC) brand by American Sales and Marketing (ASM) for the purpose of creating a line of retail food products to be sold in grocery stores, much like those offered by Boston Market and P. F. Chang.

But, as is so often the case, current events are echoes of past experience if only we pay attention. In this case, the ultimate clue that foreshadowed the propensity of women to reject Donald Trump in 2020, lies outside the political area. Instead it is embedded in a 1998 business case involving the licensing of the Chuck E. Cheese (CEC) brand by American Sales and Marketing (ASM) for the purpose of creating a line of retail food products to be sold in grocery stores, much like those offered by Boston Market and P. F. Chang.

Before executing the license agreement, ASM did its due diligence, contracting with a market research firm to provide concept guidance related to the children’s food market and the Chuck E. Cheese brand name. John Fox Consulting conducted 200 mall intercept interviews in Baltimore, Jacksonville, Chicago and Los Angeles in mid-January, 1998. The targeted interview subjects were females with at least one child age 3-12 who had purchased a frozen entrée, snack or pizza in the past month. Based on these interviews, Fox Consulting recommended ASM develop a line of CEC frozen food products. Specific items were selected through taste-tests in mid-March, 1998. Based on this analysis and projected revenues and costs, ASM executed the license and introduced the initial products in early 1999 via a subsidiary of ASM called CCF Brands (CCF being shorthand for Chuck E. Cheese Foods).

At the end of two years, annual sales reached $8.8 million, significantly less than the $33 million projected in the 1999 business plan. The problem lay not in the product itself or the initial marketing. The number of first time buyers exceeded expectations with favorable reviews related to quality and value. The problem was a dramatic fall-off of repeat customers. ASM conducted additional research to isolate the issue.

It was the findings from that analysis which also explain the migration of female voters from the Trump column. The fatal flaw in the original research was failing to understand the attitudes toward Chuck E. Cheese between a three year old and a twelve year old are quite different. In households where there were children with a gap in age, the introduction of CCF products produced chaos. While the younger child was an eager consumer, the older sibling wanted something more age appropriate. In one case, a mother reported the older child chided his younger brother repeatedly chanting, “Chuck E. Cheese is for babies.” Before I am accused of perpetuating the dated stereotype of housewives Trump has voiced in the last days of this campaign, most of the females who initially bought the product were working mothers who saw the frozen foods as a convenience, an easily prepared meal or snack. Instead, the sibling conflict produced the exact opposite effect adding to the mother’s roles as arbiter and disciplinarian.

All you have to do is substitute the name Donald Trump for CCF Brands and you could have seen the gender gap coming. In 2005, I conducted an interview with ASM president Kevin Connor in which he identified three mistakes which sealed the fate of this venture.

- Conducting mall intercepts, especially pulling aside a woman with one child, did not replicate the conditions in a typical household with multiple offspring. In concept it made sense. Injecting the products into real world environments created previously unforeseen problems.

- The marketing campaign promoted “bringing the fun of a Chuck E. Cheese restaurant into your home.” Instead, it resulted in anything but fun.

- Having a CCF Brand product in the freezer would make live easier. In reality, parents either had to prepare two different meals or spend time de-escalating sibling conflict.

So, in 2016, all of the excitement and enthusiasm at a Trump rally felt good. America First in concept was a relatively easy sell in arenas and on TV. But once tested in homes and the marketplace, the sheen quickly wore off. Trump claimed “we would get tired of all the winning,” but many of us are still waiting. And has the Trump era made life easier for most women? Ask any mother who cannot go back to work because her children are still at home taking remote classes. Or the women worried about aging parents, afraid they might be the next COVID casualties. Even before COVID, women understood they had to be peacemakers at family gatherings or social events where any moment there could be outbursts between Trump supporters and resisters. Walking on eggshells is itself exhausting.

For many women, life before Trump was turbulent enough. Many of the causes were beyond their control. Such is not the case with Trump. That is why women will make the difference in 2020. And hopefully, the next time Americans are faced with a similar choice, instead of looking to Rachel Maddow or Sean Hannity for guidance, they first seek out an animatronic rodent named Chuck E. Cheese.

For what it’s worth.

Dr. ESP