There has not been a lot of good news lately; so, the announcement of the Supreme Court decision in Bostock v. Clayton County, Georgia was reason for celebration on several levels. For me personally, it overcame one of my worst cases of writer’s block since I began blogging five years ago. My first draft on this topic was penned (intentional wording) on May 30, 2020 and was originally titled “Strict v. Selective.” The central theme being how some current justices, who wear the label “strict constructionists” on the sleeves of their robes, apply the principle selectively when it serves their ideological purposes. No case could have made this more clear than yesterday’s decision to include protection of the LGBT+ community under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

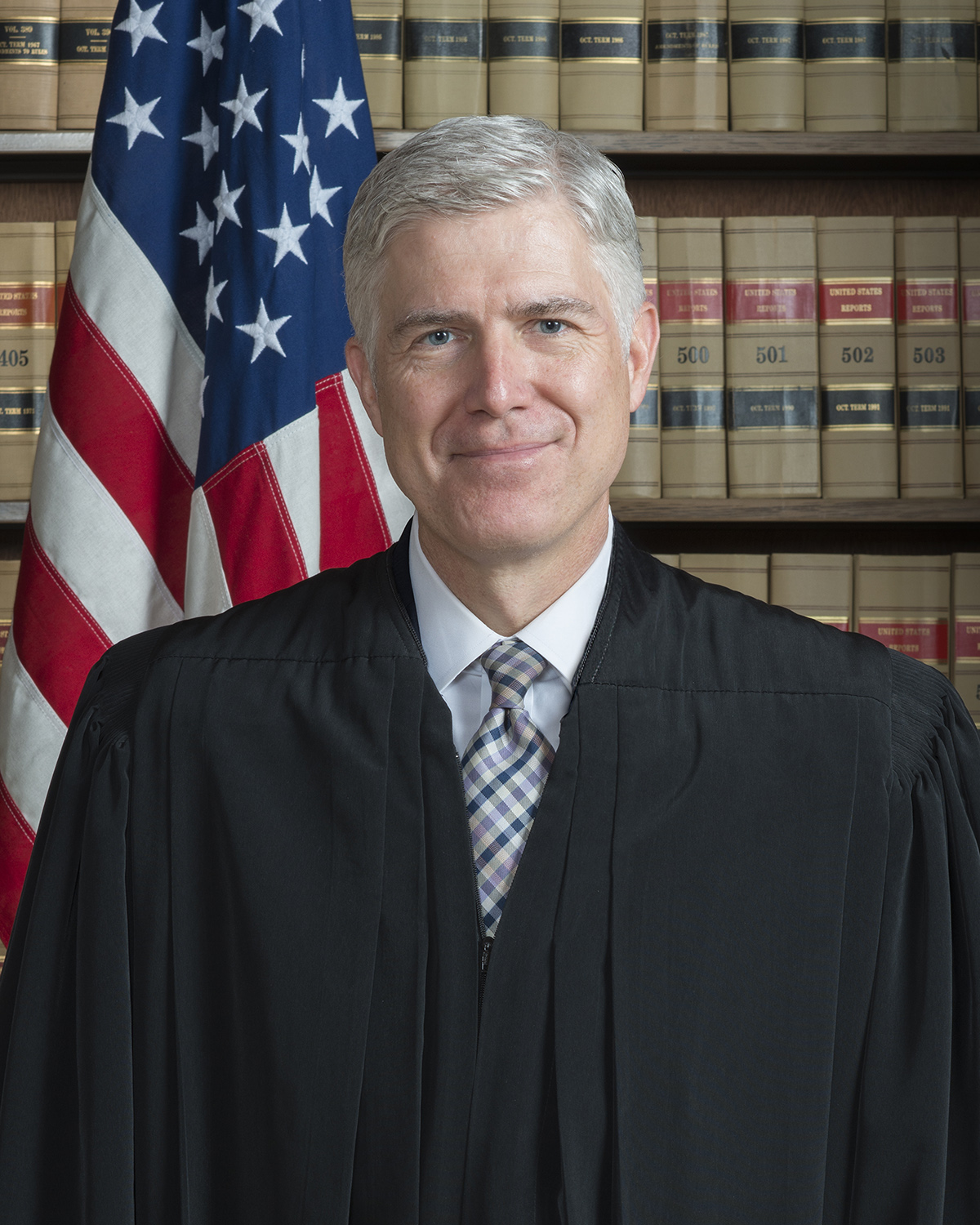

More importantly, it was not Neil Gorsuch’s opinion on behalf of the 6-3 majority which was responsible for this author’s breakthrough. It was the two dissenting opinions. One by Justice Samuel Alito for himself and Justice Clarence Thomas. The second by rookie Justice Brett Kavanaugh. My “aha moment” came not from the specific arguments, but the judicial context on which they based their dissent. I had always thought of Supreme Court justices falling into two camps. Strict constructionists who claimed the exact language in the Constitution was the controlling factor when interpreting the drafters’ intent. And modernists, who argue the founding fathers surely understood there would be sea changes in science, technology and culture which required legal precedence take such advances into account.

More importantly, it was not Neil Gorsuch’s opinion on behalf of the 6-3 majority which was responsible for this author’s breakthrough. It was the two dissenting opinions. One by Justice Samuel Alito for himself and Justice Clarence Thomas. The second by rookie Justice Brett Kavanaugh. My “aha moment” came not from the specific arguments, but the judicial context on which they based their dissent. I had always thought of Supreme Court justices falling into two camps. Strict constructionists who claimed the exact language in the Constitution was the controlling factor when interpreting the drafters’ intent. And modernists, who argue the founding fathers surely understood there would be sea changes in science, technology and culture which required legal precedence take such advances into account.

In response to Gorsuch, Alito and Kavanaugh repeatedly focused on a different frame of reference about which I had never given much thought–textualism. Gorsuch made the majority’s case in accordance with the Freudian principle “sometimes a cigar is just a cigar.” (NOTE: There is no evidence Sigmund Freud actually said it.) In other words, when the law says employers cannot discriminate on the basis of sex, it means exactly what it says and must be obeyed. If the law was meant only to give equal weight to men and women based on the box checked on birth certificates they should have said that.

In a 184 page dissent including appendices, Alito not only accused Gorsuch of a wrongful decision, he lectured him on the definition of textualism.

It is curious to see this argument in an opinion that purports to apply the purest and highest form of textualism because the argument effectively amends the statutory text.

To make matters worse, Alito continues to dig his chasm of hypocrisy, suggesting that Title VII could not possibly apply to something that required Congress to be a body of 20th century fortune tellers. For example, this is his explanation why Title VII could not have been meant to include transgender employees.

The first widely publicized sex reassignment surgeries in the United States were not performed until 1966, and the great majority of physicians surveyed in 1969 thought that an individual who sought sex reassignment surgery was either “‘severely neurotic’” or “‘psychotic.’” It defies belief to suggest that the public meaning of discrimination because of sex in 1964 encompassed discrimination on the basis of a concept that was essentially unknown to the public at that time.

Under Alito’s “ignorance is bliss” doctrine, if not for advances in knowledge, it would still be okay to discriminate against any demographic we do not fully understand. Under this precept, I assume it would be legal for a restaurant to refuse to serve Justice Alito.

Based on this fervent belief he can read the minds of long dead patriots and legislators, should we look forward to Alito applying this same criteria to other topics which come before the bench? UCLA constitutional law professor Adam Winkler is among several legal experts to suggest Alito may some day want to take back his words. Last night, he tweeted:

Alito says that ‘sex’ must be defined exactly the way that lawmakers understood that term in 1964. I’m skeptical he’ll apply that same rule to defining what counts as ‘arms’ when reading the Second Amendment.

Kavanaugh opted to join Alito in this pit of intellectual dishonesty when he demanded that judicial review rely on the “ordinary meaning” of words. In his dissent, Kavanaugh writes:

Citizens and legislators must be able to ascertain the law by reading the words of the statute. Both the rule of law and democratic accountability badly suffer when a court adopts a hidden or obscure interpretation of the law, and not its ordinary meaning.

As in the case of Citizens United v. FEC? When then sitting on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, Kavanaugh contended that the First Amendment reference to “speech” included the “hidden or obscure interpretation” that money equals speech. Do not hold your breath waiting for Kavanaugh to side with defendants of campaign finance reform consistent with his new fidelity to strict textualism. Or to rise in support of bloggers who criticize him. After all, the text in the Constitution only protects “freedom of the press” and “freedom of speech” which in 1789 did not include digital communications.

As Freud might have said, “Sometimes an Alito and Kavanaugh are just an Alito and Kavanaugh.” Nothing more; nothing less.

For what it’s worth.

Dr. ESP